In this presentation, I aim to look at the many advances in technology

that have impacted the modern field of Graphic Design, beginning from

the Madison Avenue days of advertising, up through the present day -- to

show how firms in the industry had to overcome change in order to

survive. I will also explore the direction that these changes in

technology are taking the industry and how those looking to break into

the field are being impacted.

In an industry that has existed for

so long, and undergone so many changes, growing at the same rate as

technology -- many feel that the next step, the virtual, pay as you go

model is inevitable.

The History of Graphic Design

an interactive discussion

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Saturday, April 23, 2011

The Conceptual Image

Polish Poster Art emerged in the late 1950s, when, after years of Social Realism being all-pervasive in art, Polish artistic life suddenly became much more exciting. Although success is usually dependent on many factors, we can safely say that the Polish poster school has one person to thank - the painter, drawer and graphic artist, Henryk Tomaszewski. He quickly gained the support of young and extremely talented artists who for years dedicated themselves to poster art. Some important artists of the Polish poster school were Jozef Mroszczak, Wojciech Zamecznik, Jan Mlodozeniec, Waldemar Swierzy, Jan Lenica and Franciszek Starowieyski.

The school's success can be attributed to social, as well as artistic, conditions. The genial political climate in the country at the time was an important factor. Moreover, every possible organization, especially those in the cultural arena, were vying for posters painted by one of the famous artists.

Psychedelic art is any kind of visual artwork inspired by psychedelic experiences induced by drugs such as LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin. The word psychedelic means mind manifesting. By that definition all artistic efforts to depict the inner world of the psyche may be considered "psychedelic". In common parlance "Psychedelic Art" refers above all to the art movement of the 1960s counterculture. Psychedelic visual arts were a counterpart to psychedelic rock music. Concert posters, album covers, light shows, murals, comic books, underground newspapers and more reflected not only the kaleidoscopically swirling patterns of LSD hallucinations, but also revolutionary political, social and spiritual sentiments inspired by insights derived from these psychedelic states of consciousness.

|

| Moscoso |

|

| Moscoso |

|

| Wes Wilson |

|

| Waldemar Swierzy |

|

| Paul Davis |

|

| Robert Crumb |

|

| Paul Davis |

Push Pin Studios is a graphic design and illustration studio formed in New York City in 1954. Cooper Union graduates Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast, Reynold Ruffins, and Edward Sorel founded the studio.

After graduating from Cooper Union, Sorel and Chwast worked for a short time at Esquire magazine, both being fired on the same day. Joining forces to form an art studio, they called it "Push Pin" after a mailing piece, The Push Pin Almanack, which they self-published during their time at Esquire. Sorel and Chwast used their unemployment checks to rent a cold-water flat on East 17th Street in Manhattan. A few months later, Glaser returned from a Fulbright Fellowship year in Italy and joined the studio.

The bi-monthly publication The Push Pin Graphic was a product of their collaboration. A distinctive quality of Push Pin's early illustration work was a "bulgy" three-dimensional line.

Sorel left Push Pin in 1956, the same day the studio moved into a much nicer space on East 57th Street. For twenty years Glaser and Chwast directed Push Pin, while it became a guiding reference in the world of graphic design. Today, Chwast is principal of The Pushpin Group, Inc.

The exhibition "The Push Pin Style" traveled to the Museum of Decorative Arts of the Louvre, as well as numerous cities in Europe, Brazil, and Japan in 1970–72.

Push Pin has influenced generations of graphic designers and illustrators. John Alcorn (in the late 1950s), Barry Zaid (1969–1975), and Paul Degen (1970s) spent time at Push Pin early in their careers.

|

| Seymour Chwast |

|

| Milton Glaser |

|

| Seymour Chwast |

|

| Milton Glaser |

More on the Conceptual Image:

http://www.csun.edu/~pjd77408/DrD/Art461/LecturesAll/Lectures/PublicationDesign/postmodernTime/ConceptualImage.html

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

The New York School

Paul Rand

Paul RandThe American graphic designer Paul Rand (real name: Peretz Rosenbaum) was born in New york in 1914. Between 1929 and 1934, Paul Rand studied in New York at the Pratt Institute, the Parsons School of Design, and the Art Students League. A pioneer of American graphic design, Paul Rand was influenced in his early work by Cubism and Constructivism as well as the Bauhaus, applying the principles learned from these avant-garde schools of art to graphic design. From 1936 to 1941, Paul Rand was art director of "Esquire" and "Apparel Arts" magazines while from 1938-1945 he also designed the acclaimed covers of "Direction" magaine. From 1941 until 1954 Paul Rand was art director of the William H. Weintraub advertizing agency in New York. From 1956 Paul Rand freelanced as a graphic designer and consultant for Westinghouse and IBM. Paul Rand was the designer who developed so many of the celebrated logos of such big companies and famous institutions as Westinghouse, NeXT Computer, IBM, United Parcel Service (UPS), the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and Yale University.

In addition, Paul Rand found time to be a professor of graphic design at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Paul Rand is the author of several important books on design, including "Thoughts on Design" (1947), "Design and the Play Instinct" (1955), "A Designer's Art" (1985), and "Design, Form and Chaos" (1993).

In addition, Paul Rand found time to be a professor of graphic design at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Paul Rand is the author of several important books on design, including "Thoughts on Design" (1947), "Design and the Play Instinct" (1955), "A Designer's Art" (1985), and "Design, Form and Chaos" (1993). Saul Bass

Saul Bass (1920-1996) was not only one of the great graphic designers of the mid-20th century but the undisputed master of film title design thanks to his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger and Martin Scorsese.

When the reels of film for Otto Preminger’s controversial new drugs movie, The Man with the Golden Arm, arrived at US movie theatres in 1955, a note was stuck on the cans - "Projectionists – pull curtain before the titles".

Until then, the lists of cast and crew members which passed for movie titles were so dull that projectionists only pulled back the curtains to reveal the screen once they’d finished. But Preminger wanted his audience to see The Man with the Golden Arm’s titles as an integral part of the film.

The movie’s theme was the struggle of its hero - a jazz musician played by Frank Sinatra - to overcome his heroin addiction. Designed by the graphic designer Saul Bass the titles featured an animated black paper-cut-out of a heroin addict’s arm. Knowing that the arm was a powerful image of addiction, Bass had chosen it – rather than Frank Sinatra’s famous face - as the symbol of both the movie’s titles and its promotional poster.

That cut-out arm caused a sensation and Saul Bass reinvented the movie title as an art form. By the end of his life, he had created over 50 title sequences for Preminger, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, John Frankenheimer and Martin Scorsese. Although he later claimed that he found the Man with the Golden Arm sequence "a little disappointing now, because it was so imitated".

Even before he made his cinematic debut, Bass was a celebrated graphic designer. Born in the Bronx district of New York in 1920 to an emigré furrier and his wife, he was a creative child who drew constantly. Bass studied at the Art Students League in New York and Brooklyn College under Gyorgy Kepes, an Hungarian graphic designer who had worked with László Moholy-Nagy in 1930s Berlin and fled with him to the US. Kepes introduced Bass to Moholy’s Bauhaus style and to Russian Constructivism.

After apprenticeships with Manhattan design firms, Bass worked as a freelance graphic designer or "commercial artist" as they were called. Chafing at the creative constraints imposed on him in New York, he moved to Los Angeles in 1946. After freelancing, he opened his own studio in 1950 working mostly in advertising until Preminger invited him to design the poster for his 1954 movie, Carmen Jones. Impressed by the result, Preminger asked Bass to create the film’s title sequence too.

Now over-shadowed by Bass’ later work, Carmen Jones elicited commissions for titles for two 1955 movies: Robert Aldrich’s The Big Knife, and Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch. But it was his next Preminger project, The Man with the Golden Arm, which established Bass as the doyen of film title design.

Over the next decade he honed his skill by creating an animated mini-movie for Mike Todd’s 1956 Around The World In 80 Days and a tearful eye for Preminger’s 1958 Bonjour Tristesse. Blessed with the gift of identifying the one image which symbolised the movie, Bass then recreated it in a strikingly modern style. Martin Scorsese once described his approach as creating: "an emblematic image, instantly recognisable and immediately tied to the film".

In 1958’s Vertigo, his first title sequence for Alfred Hitchcock, Bass shot an extreme close-up of a woman’s face and then her eye before spinning it into a sinister spiral as a bloody red soaks the screen. For his next Hitchcock commission, 1959’s North by Northwest, the credits swoop up and down a grid of vertical and diagonal lines like passengers stepping off elevators. It is only a few minutes after the movie has begun - with Cary Grant stepping out of an elevator - that we realise the grid is actually the façade of a skyscraper.

Equally haunting are the vertical bars sweeping across the screen in a manic, mirrored helter-skelter motif at the beginning of Hitchcock’s 1960 Psycho. This staccato sequence is an inspired symbol of Norman Bates’ fractured psyche. Hitchcock also allowed Bass to work on the film itself, notably on its dramatic highpoint, the famous shower scene with Janet Leigh.

Assisted by his second wife, Elaine, Bass created brilliant titles for other directors - from the animated alley cat in 1961’s Walk on the Wild Side, to the adrenalin-laced motor racing sequence in 1966’s Grand Prix. He then directed a series of shorts culminating in 1968’s Oscar-winning Why Man Creates and finally realised his ambition to direct a feature with 1974’s Phase IV.

When Phase IV flopped, Bass returned to commercial graphic design. His corporate work included devising highly successful corporate identities for United Airlines, AT&T, Minolta, Bell Telephone System and Warner Communications. He also designed the poster for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

To younger film directors, Saul Bass was a cinema legend with whom they longed to work. In 1987, he was persuaded to create the titles for James Brooks’ Broadcast News and then for Penny Marshall’s 1988 Big. In 1990, Bass found a new long term collaborator in Martin Scorsese who had grown up with – and idolised - his 1950s and 1960s titles. After 1990’s Goodfellas and 1991’s Cape Fear, Bass created a sequence of blossoming rose petals for Scorcese’s 1993’s The Age of Innocence and a hauntingly macabre one of Robert De Niro falling through the sinister neons of the Las Vegas Strip for the director’s 1995’s Casino to symbolise his character’s descent into hell.

Saul Bass died the next year. His New York Times obituary hailed him as "the minimalist auteur who put a jagged arm in motion in 1955 and created an entire film genre…and elevated it into an art."

Bradbury Thompson

Bradbury Thompson (1911-1995) was truly one of the giants of 20th-century graphic design, and was recognized for his achievements by every major American design organization: National Society of Art Directors of the Year Award (1950), AIGA Gold Medal Award (1975), Art Directors Hall of Fame (1977) In 1983, he received the Frederic W. Goudy Award from RIT. A wonderful essay published by the Art Directors Club asks: "How did he become 'architect of prizewinning books, consulting physician to magazines,' pre-eminent typographer, designer of stamps, multiple medalist? It all started in Topeka..."

He was born in 1911 in Topeka, where he attended Washburn College, graduating in 1934. After a brief period as a designer at Capper Publications, where he thoroughly learned every aspect of printing production, Thompson moved to New York in 1938. Over the next sixty-some years he unfurled an astonishing talent and embraced every graphic design opportunity he could. He worked as art director at the Rogers-Kellogg-Stillson printing firm and then at Mademoiselle magazine, consulted and designed for Westvaco Corporation, designed a new alphabet, and began a teaching career at Yale University, where he stayed for many years.

His career was marked by many triumphs, but three stand out prominently as exemplars of his versatility. As the designer of more than 60 issues (1939-62) of Westvaco Inspirations, a promotional magazine published by the Westvaco Paper Corporation, he reached many thousands of typographers, print buyers, and students. He had an uncanny ability to merge and blend modernist typographic organization with classic typefaces and historic illustrations, all seasoned with affectionate sentiment and impeccable taste. Working with modest resources, he saw himself as teacher and guide.

Herb Lubalin

Herb Lubalin For almost 20 years, Herb Lubalin embodied what was best in American typography. Though a soft-spoken presence, Lubalin was in fact a master communicator with a deep grasp of the subtleties of human interaction. Lubalin received his education from the Cooper Union School in New York, where he was so successful that they named a department after him: the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography. In 1945 he accepted a position as art director at Sudler and Hennessey, and in 1955 was promoted to vice president. In 1964, Lubalin left to establish his own company. He designed with the intent to communicate clearly and creatively. Rejecting the functionalist philosophy embraced by his European counterparts, he opted instead for a style that is more expressive, more communicative. Lubalin's portfolio includes advertising, packaging, editorial design, signage, typeface design, and postage stamps. Lubalin was an editorial designer for the 'Saturday Evening Post,' 'Fact,' 'Eros,' and 'Avant-Garde.' 'Avante-Garde' was dear to his heart because it represented the progressive ideals of the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and the youth culture of the time: ideals which Lubalin shared. The typeface, Avant-Garde, that Lubalin designed for the masthead of the magazine, went commercial in 1970 and has since become one of the most popular fonts in current use.

George Tscherny

George TschernyGeorge Tscherny’s work has ranged from the design of a commemorative stamp for the U.S. Postal Service to vast identification programs for such corporations as W. R. Grace & Company and Texas Gulf, Inc. His client list has included ibm, Johnson & Johnson, Mobil, and Air Canada.

Mr. Tscherny began his career in 1950 as a packaging designer with Donald Deskey & Associates. He then joined George Nelson & Associates, eventually becoming head of the graphics department. In 1955, he opened his own office, and shortly thereafter, was appointed consultant to the Ford Foundation, with design responsibility for all publications.

His work is represented in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York; and Kunstgewerbemuseum, Zurich. In 1992, the Visual Arts Museum in New York honored him with a retrospective of his work.

An extensive selection of his work is deposited in the print archive and the electronic database of the Cooper Union School of Art. Over 1,000 posters and other examples of work are included in the agi archives of the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

See Also:

Alvin Lustig

Labels:

Alvin Lustig,

Bradbury Thompson,

George Tscherny,

Herb Lubalin,

New York,

paul rand,

saul bass,

SVA

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Bauhaus

A school of art, design and architecture founded in Germany in 1919. Bauhaus style is characterized by its severely economic, geometric design and by its respect for materials.

The Bauhaus school was created when Walter Gropius was appointed head of two art schools in Weimar and united them in one. He coined the term Bauhaus as an inversion of 'Hausbau' - house construction. Gropius wanted to create a new unity of crafts, art and technology at a school with an international and interdisciplinary orientation. Its goal was the building as a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Through the innovative methods of an integrated way of teaching art, the idea was to equally prepare young artists in theory and practice for the new task.

Teaching at the school concentrated on functional craftsmanship and students were encouraged to design with mass-produced goods in mind. Studies at the Bauhaus began with the obligatory preliminary course, which conveyed methods for working with artistic material using a new pedagogical and sometimes experimental approach. This was followed by training in the workshops that largely eliminated the separation between work and theory. The goal of the education was to apply what had been learned in the theory of building.

Teaching at the school concentrated on functional craftsmanship and students were encouraged to design with mass-produced goods in mind. Studies at the Bauhaus began with the obligatory preliminary course, which conveyed methods for working with artistic material using a new pedagogical and sometimes experimental approach. This was followed by training in the workshops that largely eliminated the separation between work and theory. The goal of the education was to apply what had been learned in the theory of building.

The heart of the education was apprenticeship in the workshops, which offered a broad spectrum ranging from the processing of glass to the use of wood, ceramics and metal to stagecraft, typography, photography and advertising. The workshops were initially headed by the dual team of a craftsman as the work master and an artist as the master of form in order to guide art and technology into a new unity. The goal of the workshop activities was to apply the theory of building.

The small, international school – which very quickly made a name for itself – had an active political and cultural life that integrated all of the arts. Modern lifestyles were tested, women were allowed to study outside of the women’s classes and a libertarian approach prevailed. The parties, which were celebrated on the birthday of Walter Gropius and other occasions, were also legendary. Enormously controversial and unpopular with right wingers in Weimar, the school moved in 1925 to Dessau.

The Bauhaus moved again to Berlin in 1932 and was closed by the Nazis in 1933. The school had some illustrious names among it's teachers, including Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer. Its influence in design of architecture, furniture, typography and weaving has lasted to this day - the look of the modern environment is almost unthinkable without it. Like no other institution in Germany, the Bauhaus represents the modern age in the 20th century.

Interview with Wilfred Franks (one of the few surviving students from the Bauhaus, dated 1999)

Interview with Wilfred Franks (one of the few surviving students from the Bauhaus, dated 1999)

The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation Today

http://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/index.php?en

A comprehensive assembled collection represents the variety of assignments given to students at the Bauhaus in Weimar (1919-1925), Dessau (1925-1932), and Berlin (1932-1933)

http://library.getty.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=76390

The Bauhaus school was created when Walter Gropius was appointed head of two art schools in Weimar and united them in one. He coined the term Bauhaus as an inversion of 'Hausbau' - house construction. Gropius wanted to create a new unity of crafts, art and technology at a school with an international and interdisciplinary orientation. Its goal was the building as a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Through the innovative methods of an integrated way of teaching art, the idea was to equally prepare young artists in theory and practice for the new task.

Teaching at the school concentrated on functional craftsmanship and students were encouraged to design with mass-produced goods in mind. Studies at the Bauhaus began with the obligatory preliminary course, which conveyed methods for working with artistic material using a new pedagogical and sometimes experimental approach. This was followed by training in the workshops that largely eliminated the separation between work and theory. The goal of the education was to apply what had been learned in the theory of building.

Teaching at the school concentrated on functional craftsmanship and students were encouraged to design with mass-produced goods in mind. Studies at the Bauhaus began with the obligatory preliminary course, which conveyed methods for working with artistic material using a new pedagogical and sometimes experimental approach. This was followed by training in the workshops that largely eliminated the separation between work and theory. The goal of the education was to apply what had been learned in the theory of building.The heart of the education was apprenticeship in the workshops, which offered a broad spectrum ranging from the processing of glass to the use of wood, ceramics and metal to stagecraft, typography, photography and advertising. The workshops were initially headed by the dual team of a craftsman as the work master and an artist as the master of form in order to guide art and technology into a new unity. The goal of the workshop activities was to apply the theory of building.

The small, international school – which very quickly made a name for itself – had an active political and cultural life that integrated all of the arts. Modern lifestyles were tested, women were allowed to study outside of the women’s classes and a libertarian approach prevailed. The parties, which were celebrated on the birthday of Walter Gropius and other occasions, were also legendary. Enormously controversial and unpopular with right wingers in Weimar, the school moved in 1925 to Dessau.

The Bauhaus moved again to Berlin in 1932 and was closed by the Nazis in 1933. The school had some illustrious names among it's teachers, including Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer. Its influence in design of architecture, furniture, typography and weaving has lasted to this day - the look of the modern environment is almost unthinkable without it. Like no other institution in Germany, the Bauhaus represents the modern age in the 20th century.

Interview with Wilfred Franks (one of the few surviving students from the Bauhaus, dated 1999)

Interview with Wilfred Franks (one of the few surviving students from the Bauhaus, dated 1999) The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation Today

http://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/index.php?en

A comprehensive assembled collection represents the variety of assignments given to students at the Bauhaus in Weimar (1919-1925), Dessau (1925-1932), and Berlin (1932-1933)

http://library.getty.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=76390

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

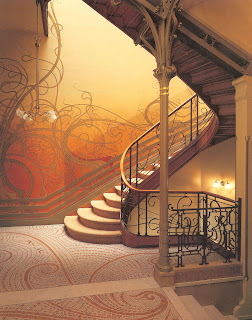

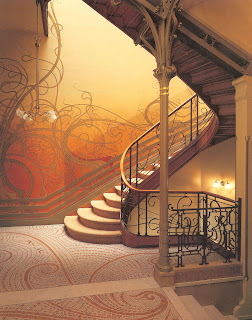

Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau is an international style of art, architecture, and design that peaked in popularity during the last decade of the 19th century through the beginning of the First World War. It was characterized by an elaborate ornamental style based on asymmetrical lines, frequently depicting flowers, leaves or tendrils, or in the flowing hair of a female. It can be seen most effectively in the decorative arts, for example interior design, glass work and jewelery. However, it was also seen in posters and illustration as well as certain paintings and sculptures of the period.

The origins of Art Nouveau are found in the resistance of William Morris to the cluttered compositions and the revival tendencies of the Victorian era and his theoretical approaches that helped initiate the Arts and crafts movement.

The movement was influenced by the Symbolists most obviously in their shared preference for exotic detail, as well as by Celtic and Japanese art. Art Nouveau flourished in Britain with its progressive Arts and Crafts movement, but was highly successful all around the world.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Art Nouveau transformed neighborhoods and whole towns around the world into remarkable examples of the contemporary, vital art of the age. Even though its style was at its zenith for just a decade, Art Nouveau permeated a wide range of the arts. Jewelery, book design, glasswork, and architecture all bore the imprint of a style that was informed by High Victorian design and craftwork, including textiles and wrought iron. Even Japanese wood-block prints inspired the development of Art Nouveau, as did the artistic traditions of the local cultures in which the genre took root.

The leading exponents included the illustrators Aubrey Beardsley and Walter Crane in England; the architects Henry van de Velde and Victor Horta in Belgium; the jewelery designer René Lalique in France; the painter Gustav Klimt in Austria; the architect Antonio Gaudí in Spain; and the glassware designer Louis C. Tiffany and the architect Louis Sullivan in the United States. Its most common themes were symbolic and frequently erotic and the movement, despite not lasting beyond 1914 was important in terms of the development of abstract art.

Furthur information:

A really informative exhibit with audio to take you through the Art Nouveau period:

http://www.nga.gov/feature/nouveau/exhibit_audio.shtm

http://artnouveau.pagesperso-orange.fr/en/index.htm

A highly functional flash site displaying the work of Klimt:

http://www.iklimt.com/

The origins of Art Nouveau are found in the resistance of William Morris to the cluttered compositions and the revival tendencies of the Victorian era and his theoretical approaches that helped initiate the Arts and crafts movement.

The movement was influenced by the Symbolists most obviously in their shared preference for exotic detail, as well as by Celtic and Japanese art. Art Nouveau flourished in Britain with its progressive Arts and Crafts movement, but was highly successful all around the world.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Art Nouveau transformed neighborhoods and whole towns around the world into remarkable examples of the contemporary, vital art of the age. Even though its style was at its zenith for just a decade, Art Nouveau permeated a wide range of the arts. Jewelery, book design, glasswork, and architecture all bore the imprint of a style that was informed by High Victorian design and craftwork, including textiles and wrought iron. Even Japanese wood-block prints inspired the development of Art Nouveau, as did the artistic traditions of the local cultures in which the genre took root.

The leading exponents included the illustrators Aubrey Beardsley and Walter Crane in England; the architects Henry van de Velde and Victor Horta in Belgium; the jewelery designer René Lalique in France; the painter Gustav Klimt in Austria; the architect Antonio Gaudí in Spain; and the glassware designer Louis C. Tiffany and the architect Louis Sullivan in the United States. Its most common themes were symbolic and frequently erotic and the movement, despite not lasting beyond 1914 was important in terms of the development of abstract art.

Furthur information:

A really informative exhibit with audio to take you through the Art Nouveau period:

http://www.nga.gov/feature/nouveau/exhibit_audio.shtm

http://artnouveau.pagesperso-orange.fr/en/index.htm

A highly functional flash site displaying the work of Klimt:

http://www.iklimt.com/

Thursday, March 3, 2011

The Arts and Crafts Movement

Industrialization resulted in a decline in creativity as designs by engineers focused on efficiency. This resulted in a move away from handicraft in favor of mass-produced goods. In reaction against the social, moral, and artistic confusion of the Industrial Revolution, the Arts and Crafts Movement arose during the later part of the nineteenth century.

The Arts and Crafts movement initially developed in England during the latter half of the 19th century. Subsequently this style was taken up by American designers, with somewhat different results. In the United States, the Arts and Crafts style was also known as Mission style.

This movement, which challenged the tastes of the Victorian era, was inspired by the social reform concerns of thinkers such as Walter Crane and John Ruskin, together with the ideals of reformer and designer, William Morris.

Their notions of good design were linked to their notions of a good society. This was a vision of a society in which the worker was not brutalized by the working conditions found in factories, but rather could take pride in his craftsmanship and skill. The rise of a consumer class coincided with the rise of manufactured consumer goods. In this period, manufactured goods were often poor in design and quality. Ruskin, Morris, and others proposed that it would be better for all if individual craftsmanship could be revived-- the worker could then produce beautiful objects that exhibited the result of fine craftsmanship, as opposed to the shoddy products of mass production. Thus the goal was to create design that was... " for the people and by the people, and a source of pleasure to the maker and the user." Workers could produce beautiful objects that would enhance the lives of ordinary people, and at the same time provide decent employment for the craftsman.

Medieval Guilds provided a model for the ideal craft production system. Aesthetic ideas were also borrowed from Medieval European and Islamic sources. Japanese ideas were also incorporated early Arts and Crafts forms. The forms of Arts and Crafts style were typically rectilinear and angular, with stylized decorative motifs remeniscent of medieval and Islamic design. In addition to William Morris, Charles Voysey was another important innovator in this style. One designer of this period, Owen Jones, published a book entitled The Grammar of Ornament, which was a source-book of historic decorative design elements, largely taken from medieval and Islamic sources. This work in turn inspired the use of such historic sources by other designers.

In time, the English Arts and Crafts movement came to stress craftsmanship at the expense of mass market pricing. The result was exquisitely made and decorated pieces that could only be afforded by the very wealthy. Thus the idea of art for the people was lost, and only relatively few craftsman could be employed making these fine pieces. This evolved English Arts and Crafts style came to be known as "Aesthetic Style." It shared some characteristics with the French/Belgian Art Nouveau movement.

However in the United States, the Arts and Crafts ideal of design for the masses was more fully realized, though at the expense of the fine individualized craftsmanship typical of the English style. In New York, Gustav Stickley was trying to serve a burgeoning market of middle class consumers who wanted affordable, decent looking furniture. By using factory methods to produce basic components, and utilizing craftsmen to finish and assemble, he was able to produce sturdy, serviceable furniture which was sold in vast quantities, and still survives. The rectilinear, simpler American Arts and Crafts forms came to dominate American architecture, interiors, and furnishings in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Today Stickley's furniture is prized by collectors, and the Stickley Company still exists, producing reproductions of the original Stickley designs.

The term Mission style was also used to describe Arts and Crafts Furniture and design in the United States. The use of this term reflects the influence of traditional furnishings and interiors from the American Southwest, which had many features in common with the earlier British Arts and Crafts forms. Charles and Henry Greene were important Mission style architects working in California. Southwestern style also incorporated Hispanic elements associated with the early Mission and Spanish architecture, and Native American design. The result was a blending of the arts and crafts rectilinear forms with traditional Spanish colonial architecture and furnishings. Mission Style interiors were often embellished with Native American patterns, or actual Southwestern Native American artifacts such as rugs, pottery, and baskets. The collecting of Southwestern artifacts became very popular in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Further reading: http://www.philaathenaeum.org/artbound/case6.html

http://www.artyfactory.com/art_appreciation/graphic_designers/william_morris/william_morris.html

The Arts and Crafts movement initially developed in England during the latter half of the 19th century. Subsequently this style was taken up by American designers, with somewhat different results. In the United States, the Arts and Crafts style was also known as Mission style.

This movement, which challenged the tastes of the Victorian era, was inspired by the social reform concerns of thinkers such as Walter Crane and John Ruskin, together with the ideals of reformer and designer, William Morris.

Their notions of good design were linked to their notions of a good society. This was a vision of a society in which the worker was not brutalized by the working conditions found in factories, but rather could take pride in his craftsmanship and skill. The rise of a consumer class coincided with the rise of manufactured consumer goods. In this period, manufactured goods were often poor in design and quality. Ruskin, Morris, and others proposed that it would be better for all if individual craftsmanship could be revived-- the worker could then produce beautiful objects that exhibited the result of fine craftsmanship, as opposed to the shoddy products of mass production. Thus the goal was to create design that was... " for the people and by the people, and a source of pleasure to the maker and the user." Workers could produce beautiful objects that would enhance the lives of ordinary people, and at the same time provide decent employment for the craftsman.

Medieval Guilds provided a model for the ideal craft production system. Aesthetic ideas were also borrowed from Medieval European and Islamic sources. Japanese ideas were also incorporated early Arts and Crafts forms. The forms of Arts and Crafts style were typically rectilinear and angular, with stylized decorative motifs remeniscent of medieval and Islamic design. In addition to William Morris, Charles Voysey was another important innovator in this style. One designer of this period, Owen Jones, published a book entitled The Grammar of Ornament, which was a source-book of historic decorative design elements, largely taken from medieval and Islamic sources. This work in turn inspired the use of such historic sources by other designers.

In time, the English Arts and Crafts movement came to stress craftsmanship at the expense of mass market pricing. The result was exquisitely made and decorated pieces that could only be afforded by the very wealthy. Thus the idea of art for the people was lost, and only relatively few craftsman could be employed making these fine pieces. This evolved English Arts and Crafts style came to be known as "Aesthetic Style." It shared some characteristics with the French/Belgian Art Nouveau movement.

However in the United States, the Arts and Crafts ideal of design for the masses was more fully realized, though at the expense of the fine individualized craftsmanship typical of the English style. In New York, Gustav Stickley was trying to serve a burgeoning market of middle class consumers who wanted affordable, decent looking furniture. By using factory methods to produce basic components, and utilizing craftsmen to finish and assemble, he was able to produce sturdy, serviceable furniture which was sold in vast quantities, and still survives. The rectilinear, simpler American Arts and Crafts forms came to dominate American architecture, interiors, and furnishings in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Today Stickley's furniture is prized by collectors, and the Stickley Company still exists, producing reproductions of the original Stickley designs.

The term Mission style was also used to describe Arts and Crafts Furniture and design in the United States. The use of this term reflects the influence of traditional furnishings and interiors from the American Southwest, which had many features in common with the earlier British Arts and Crafts forms. Charles and Henry Greene were important Mission style architects working in California. Southwestern style also incorporated Hispanic elements associated with the early Mission and Spanish architecture, and Native American design. The result was a blending of the arts and crafts rectilinear forms with traditional Spanish colonial architecture and furnishings. Mission Style interiors were often embellished with Native American patterns, or actual Southwestern Native American artifacts such as rugs, pottery, and baskets. The collecting of Southwestern artifacts became very popular in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Further reading: http://www.philaathenaeum.org/artbound/case6.html

http://www.artyfactory.com/art_appreciation/graphic_designers/william_morris/william_morris.html

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of the times. It began in the United Kingdom, then subsequently spread throughout Europe, North America, and eventually the world.

The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in human history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. Most notably, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. In the two centuries following 1800, the world's average per capita income increased over 10-fold, while the world's population increased over 6-fold. In the words of Nobel Prize winning Robert E. Lucas, Jr., "For the first time in history, the living standards of the masses of ordinary people have begun to undergo sustained growth. ... Nothing remotely like this economic behavior has happened before."

Starting in the later part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great Britain's previously manual labour and draft-animal–based economy towards machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways.

The introduction of steam power fueled primarily by coal, wider utilization of water wheels and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialization. The impact of this change on society was enormous.

The first Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, merged into the Second Industrial Revolution around 1850, when technological and economic progress gained momentum with the development of steam-powered ships, railways, and later in the 19th century with the internal combustion engine and electrical power generation. The period of time covered by the Industrial Revolution varies with different historians. Eric Hobsbawm held that it 'broke out' in Britain in the 1780s and was not fully felt until the 1830s or 1840s, while T. S. Ashton held that it occurred roughly between 1760 and 1830.

Some 20th century historians such as John Clapham and Nicholas Crafts have argued that the process of economic and social change took place gradually and the term revolution is a misnomer. This is still a subject of debate among historians. GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy. The Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies. Economic historians are in agreement that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals and plants.

see more

The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in human history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. Most notably, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. In the two centuries following 1800, the world's average per capita income increased over 10-fold, while the world's population increased over 6-fold. In the words of Nobel Prize winning Robert E. Lucas, Jr., "For the first time in history, the living standards of the masses of ordinary people have begun to undergo sustained growth. ... Nothing remotely like this economic behavior has happened before."

Starting in the later part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great Britain's previously manual labour and draft-animal–based economy towards machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways.

The introduction of steam power fueled primarily by coal, wider utilization of water wheels and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialization. The impact of this change on society was enormous.

The first Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, merged into the Second Industrial Revolution around 1850, when technological and economic progress gained momentum with the development of steam-powered ships, railways, and later in the 19th century with the internal combustion engine and electrical power generation. The period of time covered by the Industrial Revolution varies with different historians. Eric Hobsbawm held that it 'broke out' in Britain in the 1780s and was not fully felt until the 1830s or 1840s, while T. S. Ashton held that it occurred roughly between 1760 and 1830.

Some 20th century historians such as John Clapham and Nicholas Crafts have argued that the process of economic and social change took place gradually and the term revolution is a misnomer. This is still a subject of debate among historians. GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy. The Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies. Economic historians are in agreement that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals and plants.

see more

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)